Los 10 Mayores Ultimos Hallazgos arqueológicos

Mientras que el mundo se estremece por conflictos militares, desastres económicos y catástrofes naturales, los arqueólogos siguen realizando su trabajo habitual. La revista Archaeology, publicada por el Instituto de Arqueología de Estados Unidos, destacó los principales descubrimientos de 2012

Este año destacan los resultados obtenidos en las excavaciones tradicionales, que siguen trabajando del modo casi artesanal en el que lo vienen haciendo durante siglos, pero tambien las nuevas tecnologías como el georadar, cada vez ayudan a realizar más nuevos hallazgos y amplían las posibilidades de los investigadores.

La lista está formada por los siguientes descubrimientos.

1. Embarcación vikinga que sirvió como tumba

1. En la costa de Ardnamurchan, en el oeste de Escocia, Reino Unido, por primera vez en las islas británicas se encontró un barco funerario vikingo, que se cree que podría tener más de 1.000 años de antigüedad. El hombre, que fue enterrado con su bote, hacha, espada y lanza, probablemente había sido un vikingo de alto rango. Los vikingos hacían incursiones frecuentes en aquella zona a finales del primer milenio. Los científicos no hallaron restos de asentamientos en la región, pero suponen que el lugar del enterramiento podría haberse considerado sagrado en los tiempos antiguos.

La espada del guerrero vikingo, muy bien conservada.

ARCHAEOLOGY's editors reveal the year's most compelling stories

Any discussion of archaeology in the year 2012 would be incomplete without mention of the much-talked-about end of the Maya Long Count calendar and the apocalyptic prophecies it has engendered. With that in mind, as 2013 approaches, the year’s biggest discovery may actually be that we’re all still here—at least that’s what the editors of Archaeology continue to bet on.

However, you won’t find that story on our Top 10 list. We steered clear of speculation and focused, instead, on singular finds—the stuff, if you will—the material that comes out of the earth and changes what we thought we knew about the past. Here you’ll see discoveries that range from a work of Europe’s earliest wall art to the revelation that Neanderthals, our closest relatives, selectively picked and ate medicinal plants, and from the unexpected discovery of a 20-foot Egyptian ceremonial boat to the excavation of stunning masks that decorate a Maya temple and tell us of a civilization’s relation to the cosmos.

Then there are the discoveries that just made us wonder. What drove someone to wrap their valuables in a cloth and hide them almost 2,000 years ago? And why were people in Bronze Age Scotland gathering bones and burying them in bogs?

The finds span the last 50,000 years and cover territories from the cradle of civilization to what is today one of the world’s most populous cities. These are a few of the discoveries that speak to us of both our record of ingenuity and our humanity. The enduring question is always: Were the people behind the evidence anything like us?

Maya Sun God Masks

El Zotz, Guatemala

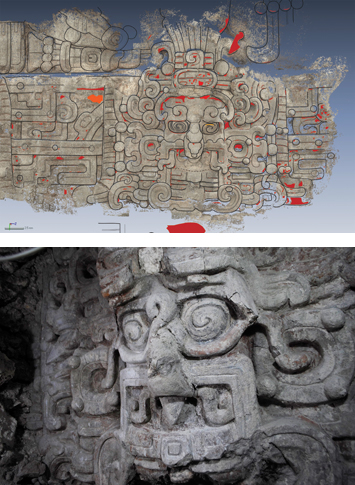

(Courtesy Stephen Houston, Brown University; Courtesy Edwin Román)

A rendering (top) of one of the masks representing the Maya sun god found at El Zotz’s Temple of the Night Sun in Guatemala shows places where crimson pigment remains. The five-foottall stucco masks (above) chart the sun’s path across the sky and decorate the exterior of the temple.

Archaeologists have unearthed a spectacular series of stucco masks at the Maya city of El Zotz. Dating to between A.D. 350 and 400, the five-foot-tall masks decorated a temple atop El Diablo pyramid, which commemorates the founder of the city’s royal dynasty. The masks were painted bright red and depict several deities, including the sun god. They show different phases of the sun as it makes its way across the sky. Between the gods are representations of Venus and other planets. “It’s a celestial symphony,” says Brown University archaeologist Stephen Houston, who co-led the excavation with Edwin Roman of the University of Texas. “The sun is closely associated with Maya kingship, and these images celebrate that link.”

El Zotz, Guatemala

Neanderthal Medicine Chest

Piloña, Asturias, Spain

the latest frontier in Neanderthal research is not the artifacts they left behind or remnants of their DNA. Rather, it is the gunk that stuck to their teeth. Karen Hardy of the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Spain and Stephen Buckley of the University of York in the United Kingdom used a variety of chemical analyses that helped uncover the first evidence that Neanderthals consumed medicinal plants. The team examined the chemicals embedded in the calcified plaque on the teeth of five Neanderthals dated to between 50,600 and 47,300 years ago from El Sidrón Cave in Spain. The analyses showed that the Neanderthals inhaled wood smoke, probably from a campfire, and that they had eaten cooked plant foods as well as the bitter-tasting medicinal plants chamomile and yarrow. “They had to have a body of knowledge about plants to select yarrow and chamomile,” says Hardy. The same analyses used in this study have the potential to be used on almost any tooth. According to Hardy, they could be used to provide direct evidence of hominin diets going back millions of years.

First Use of Poison

Lebombo Mountains, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

A notched wooden stick from South Africa’s Border Cave dating to 24,000 years ago contains the earliest evidence of humans using poison. The artifact was found in the 1970s, but new chemical analyses conducted by a research team led by Francesco d’Errico of Bordeaux University in France revealed trace amounts of substances from poisonous castor beans. The stick may have been used to apply poison to arrowheads just as a culture of modern-day hunter-gatherers called the San does today in southern Africa. According to d’Errico, poison is an important part of traditional San hunting methods because their bone-tipped arrows usually don’t cause enough damage to kill large prey on their own.

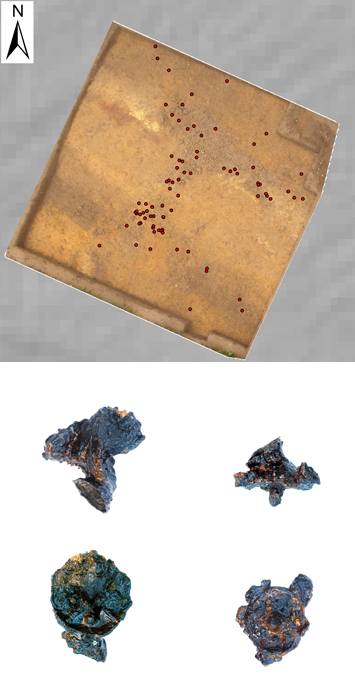

In South Africa’s Border Cave, archaeologists found ostrich eggshell beads (top), wooden digging sticks (left), and notched sticks (right) used to apply poison to arrowheads.The poison applicator is just one of several artifacts, some dating to as early as 44,000 years ago, that resemble objects used by the San. Others include a digging stick, ostrich eggshell beads, carved pig tusks, bone arrowheads, and a lump of beeswax. D’Errico’s team believes the artifacts indicate that San culture emerged about 44,000 years ago, making these artifacts the earliest link to a culture of modern humans.

The findings also clarify why it is thought that modern human behavior—loosely defined as making objects that show symbolic thinking or complex hunting methods—may have begun in Africa. Earlier evidence of such behavior has been uncovered in South Africa at sites such as Blombos Cave and Pinnacle Point, where beads, pigments, and artifacts related to fishing that date to more than 100,000 years ago have been found. Those types of artifacts, however, seem to disappear from the archaeological record at later times, indicating that those cultures may have died out. The poison and other artifacts from Border Cave, on the other hand, are the earliest that can be directly connected to an extant culture. “We think of modern humans as people who are able to change their culture all the time,” says d’Errico, “but when we have a very effective cultural adaptation, we don’t need to change.”

Aztec Ritual BurialMexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico

(Courtesy Melitón Tapia/INAH)

Archaeologists found multiple caches of skeletal remains at Templo Mayor, one of which included 45 skulls and 250 jawbones.Mexico’s Templo Mayor was a center of Aztec civic life before the Spanish conquest. In 2012, archaeologists learned more about its importance for civic death. In a grisly discovery, they excavated more than 1,000 tightly packed human bones, among them 45 skulls and 250 jawbones. There was only one complete, undisturbed skeleton, in a separate cache—a woman, lying face down, her left hand resting enigmatically on her back and her right on her abdomen. She was surrounded by more bones, including at least 10 skulls, plus ceramic and charcoal offerings.

Raúl Barrera of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History says the larger cache was probably a “closure deposit” buried as a kind of consecration after an important building phase around 1479. Because the bones are so crowded together, he says, they must have “been buried elsewhere, exhumed, and reburied here.” But not all of them. Barrera’s team excavated a volcanic slab used for human sacrifices, beneath which they found five more skulls with gaping perforations. The victims may have died on the sacrifice stone, but the holes were probably for mounting their skulls on a stake known as a tzompantli. It may all seem macabre to us, but to the Aztecs, this charnel house was, according to Barrera, “where the earthly and heavenly realms communicated with each other.”

Caesar’s Gallic Outpost

Hermeskeil, Germany

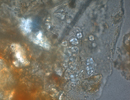

(Courtesy © Sabine Hornung, Arno Braun)

Sandal nails (above) were found at the site of a temporary Roman military camp in southwestern Germany as plotted (top) in a diagram of the area.The discovery of a collection of 75 sandal nails has led German archaeologists to the rare identification of a temporary Roman military camp near the town of Hermeskeil, near Trier, in southwestern Germany. Directed by Sabine Hornung, an archaeologist at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, the team uncovered the camp’s main gate, the flat stones that once paved its entrance, and grindstones used by the Romans to mill grain. Scattered among the paving stones were bits of metal that the team quickly identified as sandal nails. Some of the nails were quite large—as much as an inch across— and had distinct workshop marks of a type used by the army, “a sort of cross with little dots” or studs, says Hornung. “That told us it was definitely a military camp,” she adds. Ground-penetrating radar surveys showed that the camp, built to house soldiers on the move, sprawls over nearly 65 acres.

Excavated pottery sherds, both from local and imported Roman wares, date the camp to the 50s b.c., the period Julius Caesar wrote about in his memoir, The Gallic Wars. From 58 to 50 b.c., Caesar waged three campaigns against the Gallic tribes and their powerful leaders for control over the territory of Gaul, primarily modern-day France and Belgium. Taking account of the camp’s date and the distinctly Caesarean sandal nails, Hornung says, “It’s very probable it is a camp built by Julius Caesar’s legions.”

The camp sits just a few miles away from the so-called “Hunnenring,” a major Celtic hill fort with 30-foot-high walls. Such centers of military and political power made Gaul an attractive target for the Romans. By focusing their efforts on these regional centers, the Romans could exert sustained and concentrated pressure on local leaders instead of having to chase down the scattered tribes living in the German forests further to the east. Eventually this pressure, and the military victories achieved by Caesar and his legions, resulted in the conquest of Gaul and cleared the way for the general to assume sole control of the Roman Republic.

For Gunter Moosbauer, an archaeologist at Germany’s University of Osnabrück familiar with the discovery, the finds from Hermeskeil are an “archaeological thrill.” He says, “Roman field campaigns lasted just a few months, and to find one of their temporary camps is really rare."

Hermeskeil, Germany

Europe’s Oldest Engraving

Sergeac, France

The First Pots

Jiangxi Province, China

Scottish “Frankenstein” Mummies

South Uist, Scotland

2,000-Year-Old Stashed Treasure

Kiryat Gat, Israel

Oldest Egyptian Funerary Boat

Abu Rawash, Egypt

Oldest Egyptian Funerary Boat

Abu Rawash, Egypt

(Courtesy Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

Archaeologists originally mistook an ancient Egyptian funerary boat found at the cemetery of Abu Rawash for a wooden floor. The 20-foot boat dates to 2950 B.C.

Egyptologist Yann Tristant was reading a 1914 excavation report on a First Dynasty (ca. 3150–2890 B.C.) tomb at the elite cemetery of Abu Rawash when he noticed something strange. The author, legendary French archaeologist Pierre Montet, wrote that just north of the mudbrick tomb, or mastaba, he had uncovered a wooden floor. That seemed bizarre to Tristant, of Macquarie University in Sydney, because he knew that no other archaeologists have reported finding wooden floors around mastabas. Sensing a mystery, he directed his team to excavate at the same spot Montet had almost a century before. The hunch paid off and led Tristant to a pit bounded by a brick wall that held the oldest boat found in Egypt, a 20-footlong vessel dating to 2950 B.C.

It’s clear the boat played some role in the burial ceremonies of the tomb’s owner, a high-ranking official. Tristant uncovered artifacts nearby that point to a lavish funerary feast, including ceramic beer jars and bread molds. Ceremonial boats have been found at tombs at royal cemeteries; they were intended to symbolically carry pharaohs into the afterlife. But since so few boats have been found at nonroyal tombs, Tristant hesitates to speculate exactly what religious function the Abu Rawash vessel served. “It’s a good example of why we must sometimes re-excavate sites,” says Tristant. “I never would have expected to find a boat at a tomb like this.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario